Top-down and bottom-up

Scale and its discontents

One of the major sources of dysfunction in school systems is scale.

Education comes from a personal connection between two human beings. That connection can occur in many different settings: teacher and student, master and apprentice, coach and player, parent and child, just to name a few. But these connections are always one-on-one, and therefore cannot scale.

Of course, this fact doesn’t mean that a school cannot scale. It can, to a point, just like a business, a team, or a family. But there are limits, and they are hard-wired into human brains. (More on this in a moment.)

Once a group grows past a certain size, once you move from small scale to large scale, two different modes of thought emerge: top-down and bottom-up.

To be clear, at small scale, there is no top-down and bottom-up. There need not be a hierarchy in small groups, but if there is there will still be a direct connection between leader and follower. For instance, a coach may have authority over a player, but she also has a direct, personal connection with each player, and each player has a direct, personal connection with her.

However, as groups grow larger, these connections – each a relationship between two people – grow weaker. And if the group continues to grow, it reaches the point where the folks at the top of the group hierarchy (those with authority) no longer have a personal connection to everyone at the bottom. People at the bottom are truly strangers to people at the top.

So large scale systems – like public education in Texas – always lead to top-down and bottom-up modes of thought. Let’s explore that a bit more.

Top Down and Bottom Up

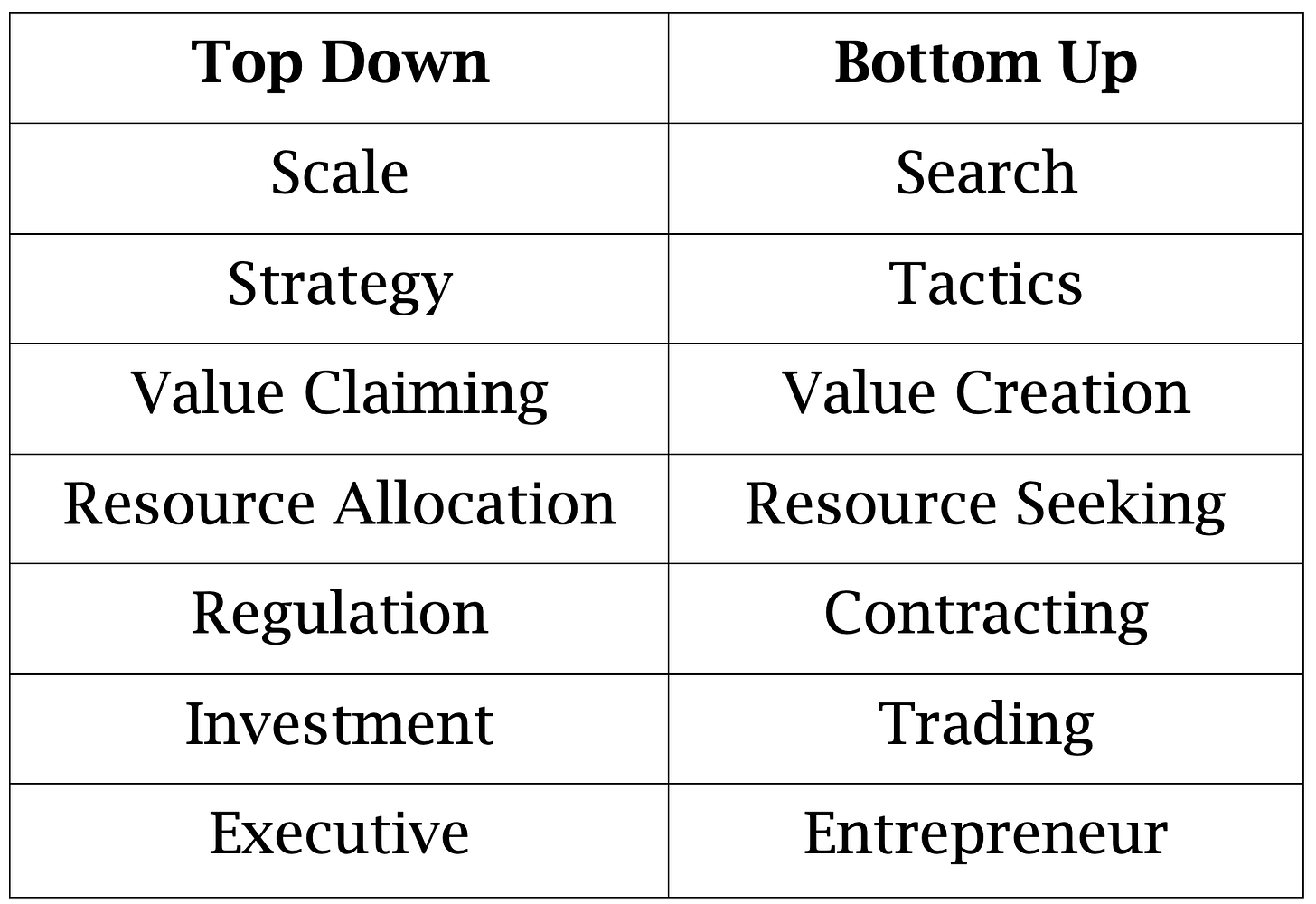

Top-Down is the dominant mode of the general staff, the corporate office, the bureaucracy, the hierarchy. Leaders of large organizations operate in a top-down mode. Top-Down is the mode of the Executive.

Bottom-Up is the dominant mode of the worker, the soldier, the plant, the entrepreneur, the market. Markets participants operate in a bottom-up mode. Bottom-Up is the mode of the Entrepreneur.

It is not possible for someone at the top of a large organization to have complete and detailed knowledge of what is going on at the bottom.

For instance, a school board may pass a rule forbidding the use of smartphones during school, but they cannot know at any given time whether everyone is, in fact, complying with this rule. Indeed, it is entirely possible that a policy issued from on high is completely at odds with the facts on the ground. It’s even possible that almost no one follows the policy!

Since it’s impossible for folks at the top to know the current state of reality in detail, they rely on reports from others, data that is “chunked” into summarized units. But whenever data is chunked, that data can be skewed:

Outliers can be ignored (even though in some cases outliers are the most important points on a graph)

Averages are used, and averages are not always meaningful (if you have your head in the oven and your feet in the freezer, your average temperature may be fine but you are not)

People make mistakes (some because of bad luck or matters beyond their control, others because they are lazy or incompetent)

People mislead (some because they don’t understand the big picture, others because they understand the big picture all too well!)

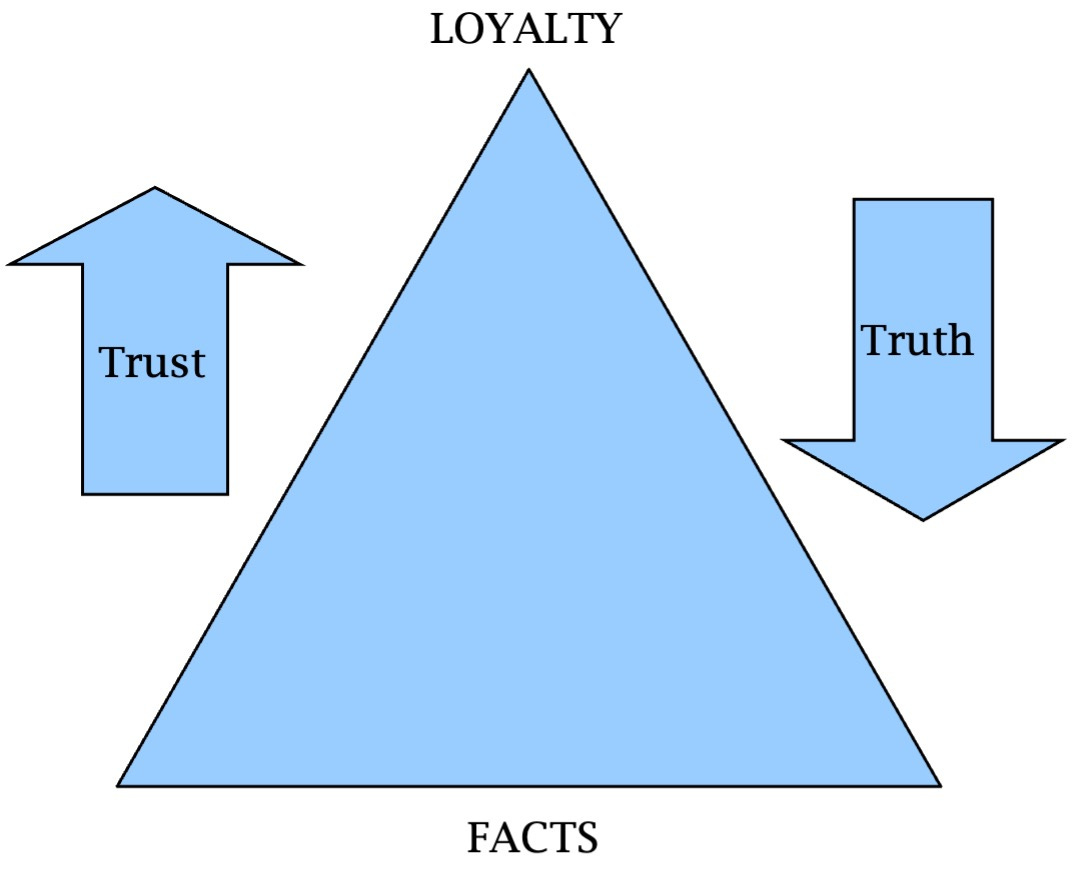

As a result, the closer you are to the top of an organization, the more you rely others, which means you rely more on trust than facts.

At the top, because a leader is too far away to personally verify the facts, they must rely on the person reporting the data, which means they must trust that person. And those folks, in turn, rely on others further down the hierarchy. Trust is key, and that puts a premium on loyalty near the top. At the bottom, there is less need for trust and loyalty as the facts are plainly visible for all to see.

The loyalty premium also changes the incentives of people as they approach the top of the organizational pyramid. Rising middle managers become more risk averse as they’re promoted because they more to lose. Because there’s no way for my boss to really know what’s going on, why tell him the brutal facts when I can say everything is hunky dory and he has no way to know otherwise?

Of course, leaders can put in place compliance mechanisms, but the more you push compliance, the more you undermine trust, driving the need for more compliance, further undermining trust, and so on in a vicious circle.

(Historical aside: Ronald Reagan famously annoyed Mikhail Gorbachev by quoting a Russian proverb, “доверяй, но проверяй,” which translates as “Trust but verify.” It was a savvy response, because it sounds like Reagan was saying he trusted Gorbachev, when in fact “verify” means, pretty much by definition, that you don’t “trust.” No wonder Gorbachev was annoyed.)

On the other hand, the bottom of the organization is driven by facts. A child comes to school this morning or doesn’t. A teacher knows how to teach prime factorization or doesn’t. A sales representative makes the sale or doesn’t. A basketball team wins the game or doesn’t. The facts are the facts, and everyone can see the truth with their own eyes.

In short, life at the bottom of an organization is driven by facts – and so by truth – and life at the top of an organization is driven by trust – and so by loyalty.

Jane Jacobs, a great 20th Century American thinker, wrote about two distinct ways of thinking – the economic and the political.

By Jacobs’ definition, large scale organizations are naturally and necessarily political. Even large corporations that claim to be 100% focused on economics are, in fact, political. The harsh truth is that its senior managers are not 100% focused on economics; they are 100% focused on keeping their job (or getting promoted), otherwise they would not be senior managers.

Let’s now take a slight diversion in the wonderful, wacky world of Oxford professor Robin Dunbar.

Robin Dunbar and His Magical Number

Dunbar began his career studying gelada baboons. He observed that a baboon group would grow, and when it reached a certain critical size, a group of males and females would split off and form a new group.

Dunbar also noticed that this critical group size was quite stable for baboons. He also read studies from other anthropologists about other species and learned that a similar phenomenon occurred for all species of non-human primates. All primate groups grow to a critical size, and then split.

Intriguingly, that group size was quite stable for a given species but varied a lot between species. If, say, orangutans had a mean group size of 30, chimps had a group size of 60 and gorillas had a group size of 12.

One of Dunbar’s insights was that this pattern – consistent within a species, variable between species – strongly indicated that group size was rooted in biology. He hypothesized that there must be a physical explanation for what he observed as a social phenomenon.

When he began to look for potential biological factors, he naturally focused on the brain. He thought perhaps group size was a function of brain size – the bigger the brain, the bigger the group.

Alas, that hypothesis didn’t fit the data. Chimps had large groups, while gorillas had small groups, even though gorilla brains were much larger than chimp brains.

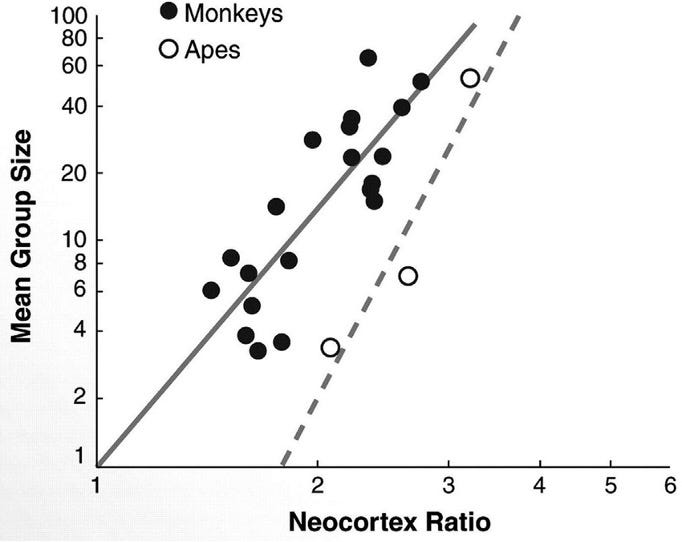

Still, Dunbar believed the brain had to be involved in some way. He decided to look at the neocortex – a specialized part of the brain that was prominent in primates. This made sense since social interaction was likely processed in the neocortex, as it is a “higher order” cognitive function unlike, say, breathing.

Dunbar gathered the data and plotted relative neocortex size against group size, and here is what he got:

The bigger your neocortex, the bigger your group size. Very nice.

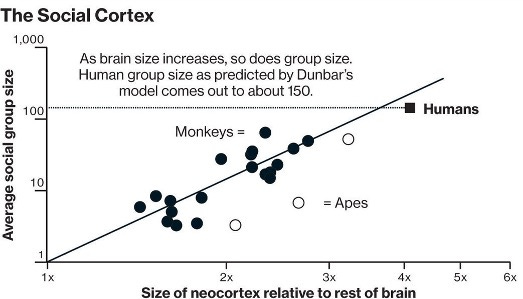

Dunbar then asked the logical next question – what about humans? After all, humans are primates, albeit ones with a freakishly big neocortex. (It’s so big, we are born 9-12 months early, well before we can walk, but while a baby’s big fat head can still fit through mom’s birth canal.)

So he extended his chart to include the human brain:

Dunbar used his mathematical model to predict that the average social group size for humans would be 150. Dunbar then noticed that this number pops up everywhere:

Estimated size of a Neolithic farming village

Splitting point of Hutterite settlements

Upper bound on the number of academics worldwide in a discipline's sub-specialization

The ideal size of an Anglican community

Basic unit size of professional armies in Roman antiquity and modern times since the 16th century

I would add others:

Upper bound on the number of family shareholders in a family business

The number of active friends in a social network (as Dunbar himself demonstrated – you can have a million Facebook friends, but you will only interact with about 100 people. In other words, you may know Cristiano Ronaldo, but he doesn’t know you.)

The size at which political parties emerged in Congress.

If you look at the groups around you, you’ll notice this number with surprising frequency. Promise.

Smitten by his discovery, Dunbar gave this number a name:

Dunbar’s Number = 150.

Dunbar’s insight that group size is limited by a physical constraint – cognitive capacity, as determined by neocortex size – led to his discovery of a fundamental unit of human interaction.

To quote Dunbar himself:

150 seems to represent the maximum number of individuals with whom we can have a genuinely social relationship.

These are people we know well enough to predict their behavior with reasonable accuracy.

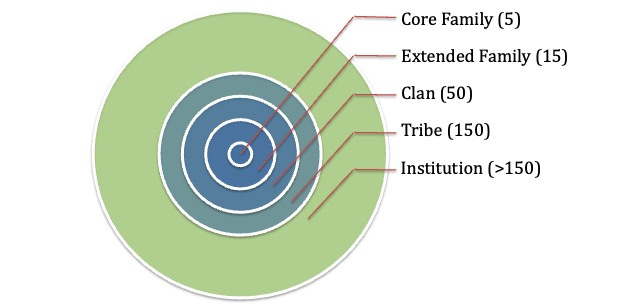

Within our group of 150, there are inner circles of increasing familiarity. You can subdivide our Dunbar group by dividing by three to get each next layer (the names are my choices, others might use call a layer something different):

Dunbar’s Number implies that so long as the group is less than 150 (plus or minus), I can know everyone reasonably well, and so coordinate and cooperate based upon my knowledge of, and experience with, others in the group.

This limit remains even as an organization expands beyond 150 people. If you are part of a group larger than Dunbar’s Number, there are group members you don’t really know: you have strangers in your group. Consequently, we can’t manage only through relationships; we also need rules to help us predict how people will behave (and they, us).

But rules are made by those in authority, and authority comes from the top. And since people at the top are still human, they are tribal and therefore only trust people in their tribe. Thus does power become concentrated at the top and decision-making become top-down in a large organization.

Put differently:

At small scale – the scale of a family – we have only a few relationships but there is a high level of intimacy and connectivity and memory. We grow up around our parents and siblings and children and watch them closely and imitate their ways and generate lots of memories (good and bad)

At a large scale – the scale of an institutions - we have more relationships, but they are less intimate, less connected, and less enduring. We generally live around, work with, and play with strangers, governed by impersonal rules imposed by strangers.

So to summarize:

Success leads to growth.

Growth leads to scale.

Scale generates institutions.

Institutions require laws.

Laws are made by a tribe of people at the top, who think top down, and imposed on people at the bottom, who live bottom up.

Success, then, inevitably leads to top-down and bottom-up modes of thought. And that’s a problem for education.

What This All Means for Education

As the public education system grows, those at the top maintain their authority. There are abut 5.5 million PK-12 public school children in Texas, but there is one and only one Education Commissioner for the State of Texas.

In addition, growth causes the gap between top and bottom to get wider. It is highly unlikely that a teacher will ever meet, much less get to know well, the Education Commissioner. It’s just math: there are about 300,000 teachers in Texas public schools. If the Commissioner had a 10-minute chat with each of them, and did nothing else 10 hours every day, 365 days a year, it would take more than 13 years for him to talk to them every Texas teacher!

And 10 minutes is not a lot of time to convey 13 years’ worth of insight.

And there are 20 times as many students.

For better or for worse, the Texas Education Agency must operate top-down, which as we saw above means it will rely on trust and prioritize loyalty.

But Dunbar’s Number means that trust and loyalty will be limited to a small tribe of people who have a relationship with the Commissioner, who in turn must be trusted by the Governor. So maybe a few dozen people have the real authority administer a massive system employing hundreds of thousands and serving millions of families.

Of course, technocrats might believe that they can still find out the “facts on the ground” using sophisticated technology and carefully constructed rules. They believe such a system can generate reliable data which can then be analyzed by smart people to make good decisions for everyone.

But they’re kidding themselves. This sort of centralized simply cannot work, even if those in control are hardworking, well-intentioned geniuses.

We don’t have to speculate about this hypothesis. In education, we’ve already run the experiment multiple times – most recently in Texas by deploying extensive, detailed regulations and a statewide measurement system (STAAR) custom built by world-class experts to assess student and teacher performance – and the system is (at best) tragically mediocre.

Legislators have also tried to improve results by creating an alternative system – charter schools – that would not be subject to all the same rules. But what we can now observe is this strategy only worked until the charter schools themselves became large scale institutions, at which point they fall prey to the same dysfunction seen in large districts – and their performance reverts to the mediocre mean.

Fundamentally, what Texas legislatures have tried to do my entire life is apply large-scale, top-down approaches to an inherently small-scale, bottom-up problem: the education of the next generation of Texans.

School choice, in the form of Education Savings Accounts, will be the first bottom-up approach to public education in Texas. Rather than rely on a top-down set of rules and measurements systems, ESAs would put resources under the control of families and rely on their agency and insight. Parents and guardians, not politicians and bureaucrats, would make decisions about the education of their children.

In place of central planning and oversight from Austin based upon fixed categories and sparse datasets, families would engage in bespoke planning and oversight that would happen in tens of thousands of homes using the deep insight into a child’s needs that only a parent can have.

(Not convinced? Try this thought exercise: compare what you know about your child to what the State of Texas has within PEIMS, its official education database. Do you know your child’s favorite color? Most hated food? Their interests, fears, and aspirations? None of that information is known to the state, and it would be creepy if it was.)

Crafting such a system will be challenging. Legislative processes, and virtually all the people engaged in them, are by avocation and training top-down thinkers. (For those new to this distinction, here’s a tell: anytime someone says the word “policy,” they are in top-down mode.) Those folks don’t really know what happens on the ground (no one can), and to the extent they have some personal knowledge it is likely to be chunked or biased.

But if they get it right – and there is reason to hope they will – legisltors will unleash a powerful force for innovation and improvement: an empowered and engaged family.

And then change will be driven from the bottom up.

For a change.