Every person with authority, confronts a tension between rules and discretion.

Do I establish a rule that determines behavior? or

Do I allow individuals discretion to make their own decisions?

Consider some examples:

As an employer, should I require regular drug testing, or let a supervisor decide whether an employee should be tested (presumably when they appear drunk or stoned)?

As a parent, should I require all kids to wake up at a specific time, or let each kid decide when they roll out of bed?

As a legislator, should I enforce a consistent set of regulations across the entire state, or leave it to local leaders to make local decisions?

As a superintendent, should I ban the use of smartphones in all schools, or leave it to a principal or individual teacher to decide whether to implement a ban in their school or classroom?

Note that in each of these cases, the goal is likely to be the same regardless of your views on the right policy:

we all want a safe and productive workplace

we all want kids to be happy and active

we all want greater human flourishing

we all want an efficient and effective educational system

Still, it is not clear that which way the issue breaks:

Does random drug testing assure a safe and productive workplace by creating a disincentive to drug use (which may compromise safety and productivity), or does it create a culture of distrust and deception (thus undermining both safety and productivity)?

Does a regular schedule help kids develop good habits that will prepare them for their future adulthood, or does it impair cognitive development of young people who need more sleep (some more than others)?

Does a system of uniform statewide regulations improve human flourishing by creating a “single market” that allows producers to achieve greater economies of scale and lower the price of goods and services to consumers, or does it undermine local, tight-knit communities by replacing small, local firms with large, distant corporations who drive out competition and risk destroying the community’s social and human capital?

Does a smartphone ban help minimize distractions during school, thus making the learning environment better for all, or does it create a hostile environment that turns teachers and other students into “phone police” and keep kids from developing the will power they will need to resist the allure of social media once they leave campus?

See the complexity here? It’s almost as if there’s no easy answers!

Before discussing rules and discretion in the context of education, there’s another twain that is intimately linked to it: options and commitment.

Often, decisions involve choosing between making a commitment and leaving your options open.

Do I buy an iPhone today, or do I wait for the new and improved version?

Do I take a job offer, or do I keep looking to see if I can get a better one?

Do I get married, or keep playing the field?

Every day we are faced with decisions, and in most cases, we have a choice: commit to a particular option or wait and see if something (presumably better) comes along later.

Of course, commitment has an impact on behavior. In fact, commitment may be the most important impact on behavior.

In a famous story that may be apocryphal, Hernan Cortes landed in Mexico in 1519 with his crew of 400. Cortes was rightfully worried about a possible mutiny; after all, he had just led them on a mutiny from the command of Velazquez, the governor of Cuba and Cortes' sworn enemy. Having mutinied once, who was to say they wouldn't do the same thing again? Moreover, they weren't exactly thrilled about being led to this strange, dangerous new land filled with savage Aztecs.

So Cortes decided that he’d force a commitment: he burned his boats.

With such a commitment, Cortes and his crew had no choice but to fight the Aztecs to establish the security needed to build new boats for their return.

Using another analogy, when it comes to breakfast, there is a difference between a pig and a chicken.

The chicken is involved (eggs), but the pig is committed (bacon). The chicken has options after breakfast. The pig: not so much.

Okay, but what do options and commitment have to do with rules?

Just this: rules require commitment. For a rule to be a rule, you must make a commitment to it. You foreclose other options. A commitment to a rule limits your discretion.

Indeed, rules only become rules if they’re committed to in advance – otherwise they’re not a rule, they’re more of a guideline. You see this in many contexts:

The rule of law is activated by a commitment to live in a specific location.

The rules of marriage are activated by a commitment to marry.

The rules of work are activated by a commitment to a job.

The rules of a church are activated by a commitment to a creed.

Now, we rarely go “all in” on a commitment – in most situations, we make a limited commitment, like “I will agree to obey orders, but if it violates my conscience I reserve the right to object.”

This approach makes sense, and it reinforces the core point: rules apply only to the extent of a commitment.

So, to recap:

Rules require an upfront commitment.

Rules are only effective to the extent of that commitment.

Discretion, on the other hand, requires that you forgo commitment. Discretion says, “I’m not committed to any particular course of action but will make my decision based upon the facts at the time I have to decide.” Discretion preserves options.

But wait – if discretion preserves options, and having more options is good, why isn’t discretion always better than having rules? Why commit to rules at all?

Really, just one reason: scale.

All human large-scale systems rely on rules to maintain their effectiveness, power, and cohesion. It’s back to stuff we discussed in Top Down vs. Bottom Up, especially Dunbar’s Number.

As we saw in Top-Down and Bottom-Up, groups larger than Dunbar’s Number – that is, greater than 150 – need rules. These rules impose a cost, as we need people to create and enforce the rules, which in turn adds to the scale of the firm, creating even more need for more rules (and more rule enforcers, and so on).

But more importantly, lots of rules means lots of commitment, which is why big organizations limit discretion. Otherwise people would just do what they want. And we can’t have that, now can we?

The result is what I like to call UPOL, the Universal Preference of Organizational Leaders:

Rules for thee, discretion for me.

In public education, you see UPOL clearly in the interaction between various levels of the system. Superintendents will lash out at the state officials for over-regulating their local schools, and then those same Superintendents will themselves turn around and impose severe restrictions on principals and teachers.

You see, everyone is in favor of local control until they’re in control.

Often, this switch results from the incentive structure of institutional elites (i.e. the people who run the “bigs” – big governments, big corporations, big non-profits, big religions, big media, etc.). These folks are often driven by a desire for status and power (and tend to win the competition for organizational authority because of that drive). Many are socialized from an early age to believe that important decisions must be made by important people. This view might sound plausible to an educated elite (can we really trust the great unwashed masses to make good decisions?) but fails even the most basic test: does it apply to our own life?

What are the most important decisions in your life? Where to live? Who to marry? What job to take? What to believe? Do you want any of critical decisions about your life to be made by some remote, centralized authority? Of course not. In fact, despite the existence of social media influencers, I believe that the rich, famous, and powerful are generally the WORST people to entrust with the most important decisions in our lives.

Anyway, this interplay between rules, discretion, commitment, options, and scale have a profound and ongoing impact on public education in Texas.

We are trying to run a large scale system – more than 5 million school-aged kids – and that requires rules. Rules, in turn, require commitments from the participants. (This reality helps explain why those involved in public education feel so passionate about their engagement. Commitment is essential to its functioning.)

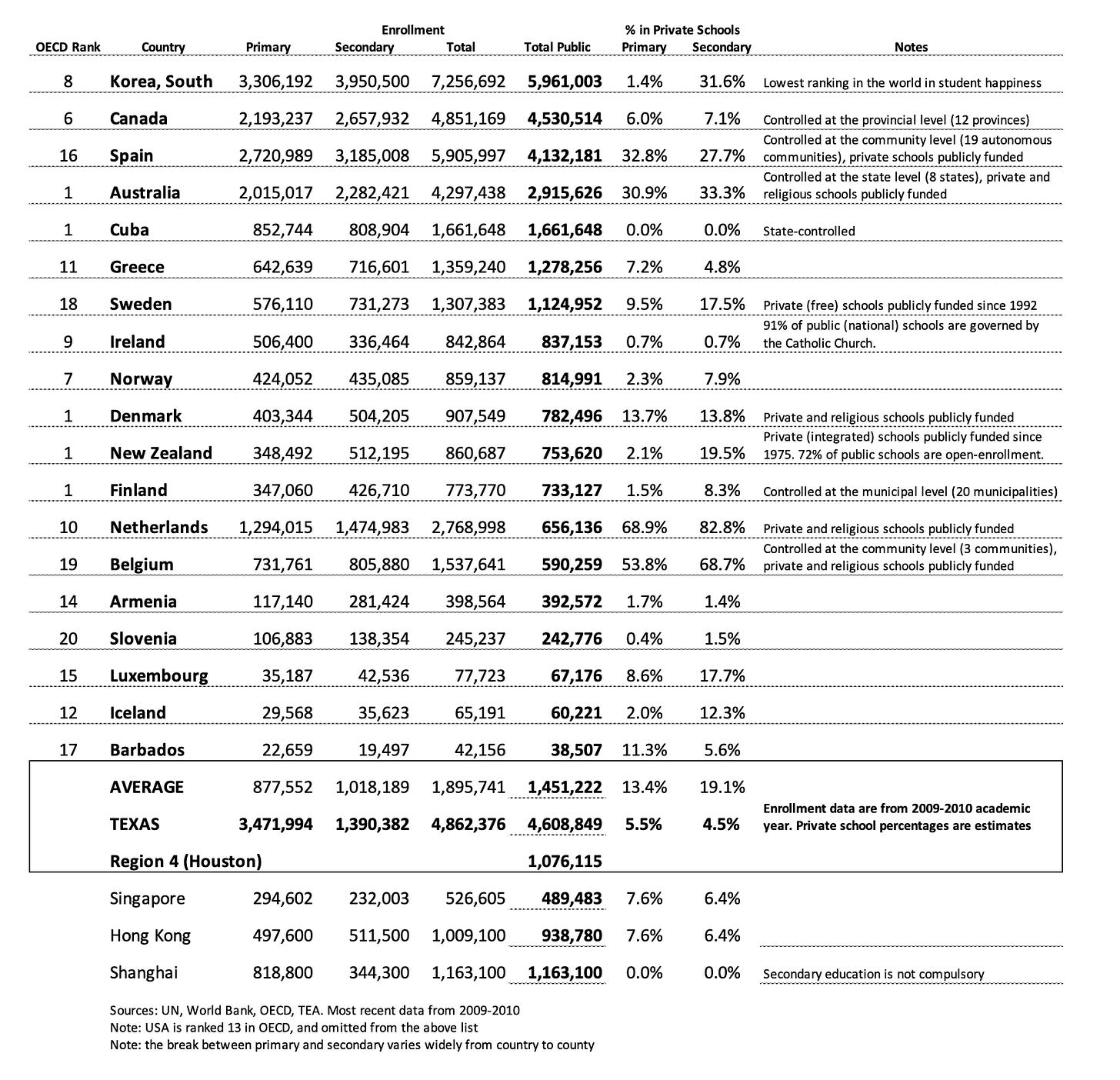

Scale is the undoing of our education system system in Texas. In fact, I can find no system anywhere in the world (with the possible exception of South Korea, which has a number of weird quirks and not really one we want to emulate) that attempts to run a centralized education system as large as Texas (this data is a bit old, but the point is still relevant):

Why? Here’s my view:

As any human system grows, our limited ability to form trusted relationships necessarily means that decision-making will be centralized (recall from Top-Down and Bottom-Up the tribal nature of all institutional elites).

At the same time, rules are necessary to run a large-scale system, so the main work of its leaders will be to make rules – even as they become more distant and disconnected from the reality on the front lines.

On top of that, commitment is required from teachers, parents, students, and education sector middle-managers to make this kind of rule-driven system work. But because of the scale and complexity of the system, their commitment is practically indistinguishable from blind faith, as no one fully understands cause and effect from the top of this system (try understanding the effect of Texas school finance laws on student test scores, a math problem so impenetrable that today David Hilbert would have undoubtedly included in his famous list).

So over the past 5 decades, we have evolved a large scale, routinized, rule-based, centralized, top-down system requiring unquestioning commitment from producers and consumers alike.

Fair enough. But while that system appears to work fine for many families, it is increasingly clear that does not work for an increasing number.

Those families need fewer rules and more discretion. And that’s the promise of school choice.

Of course, whether Texas can deliver on that promise remains to be seen…